Part IIIb: The Work

M. Bunch Washington and the Discipline of Light

By Mark Rengers

Before considering the discipline and material intelligence of his work, it helps to situate McCleary “Bunch” Washington (1937–2008) within his historical and artistic context. Born in Philadelphia, Washington trained at the Barnes Foundation and the Philadelphia Museum School of Art before moving to New York City in the early 1960s. A painter, collage artist, and scholar, he belonged to a generation of African American artists whose careers unfolded largely outside the institutions that defined mainstream recognition at the time. Washington is perhaps best known for his groundbreaking monograph The Art of Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual (1972), the first major book published on an African American visual artist, as well as for his own innovative Transparent Collages, works that fuse light, material, and embedded objects into shifting, luminous environments. His career bridged practice and advocacy, making him both an artist and a champion for others whose work demanded attention.

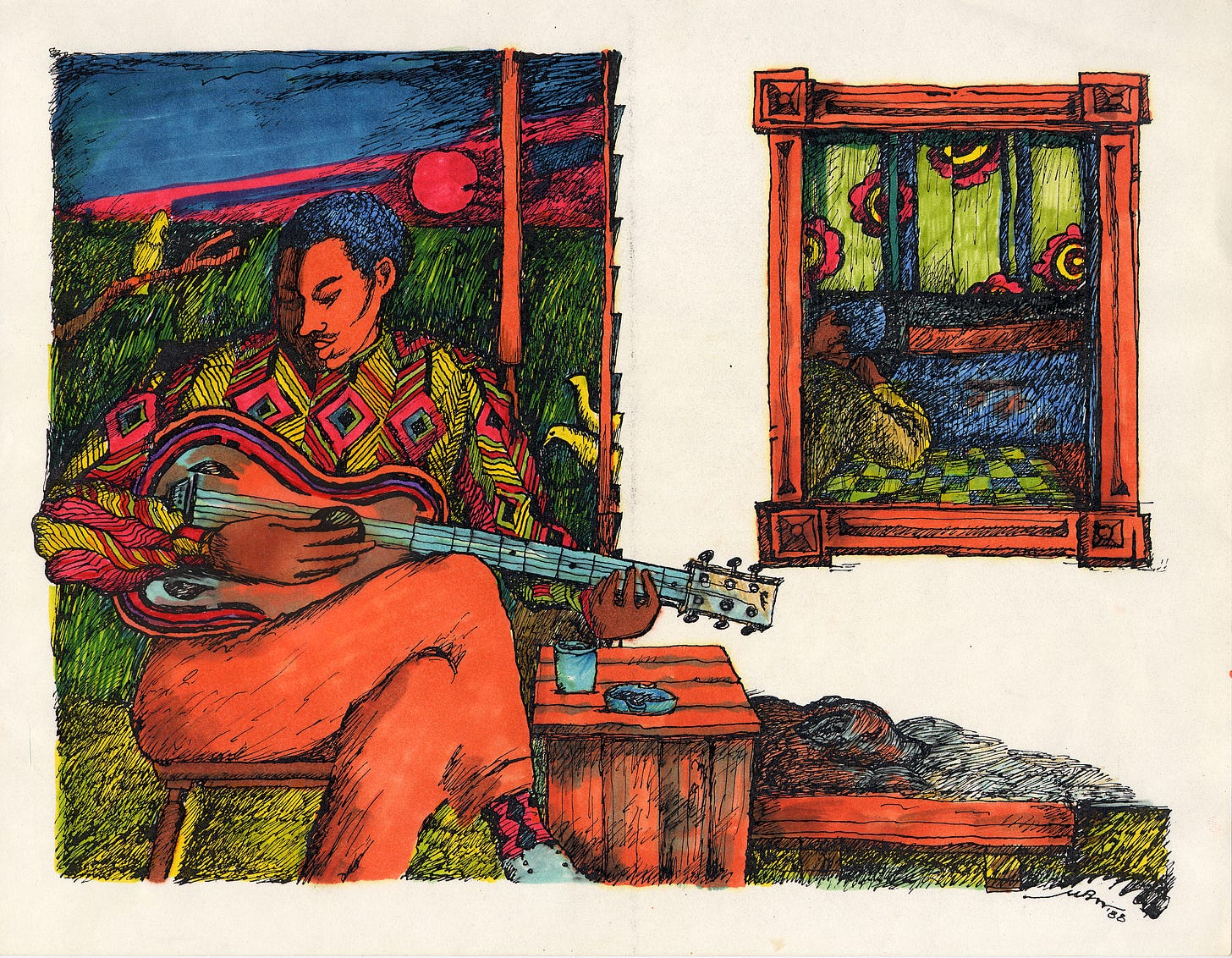

“Self Portrait”, M. Bunch Washington, 1988

If absence sharpened the urgency of M. Bunch Washington’s life, discipline shaped how he answered it.

Washington came of age with a rigorous understanding of art as structure, study, and responsibility. His training at the Barnes Foundation, followed by study at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art, placed him squarely within a tradition that demanded close looking, historical fluency, and an understanding of how cultures speak to one another across time.

When Washington moved to New York City in the early 1960s, he entered a world dense with artists, ambition, and contradiction. Like many painters of his generation, he supported himself through practical work, including framing, while carving out time to paint. It was in a frame shop that he first encountered the work of Romare Bearden, an encounter that would alter the course of his life.

Washington later wrote about the moment he held one of Bearden’s works in his hands. He was so struck by what he saw that he misaligned another frame he was working on and was fired for the mistake. The loss of the job mattered less than the recognition. Here, in Bearden’s work, Washington saw ideas he had studied formally at the Barnes brought to life, the interlocking of cultures, histories, and forms into something unmistakably whole.

That recognition did not lead him away from his own practice. It refined it.

Washington’s work would come to be most closely associated with his Transparent Collages, objects that defy easy categorization as either painting or sculpture. These works are not simply images. They are environments of light.

“Curlean”, M. Bunch Washington

In 1975, Romare Bearden wrote about Washington’s work for an exhibition brochure at Off Broadway Gallery. His words are not praise in passing. They are careful observation from one artist who understood the labor of another.

“Figures and objects float in the luminous depths of Bunch Washington’s Transparent Collages,” Bearden wrote, “fascinating assemblages of textures and colors changing and expanding as the light caresses them at varying angles and at varying degrees of intensity.”

“Sophisticated Lady I”, M. Bunch Washington (courtesy Violet & Les Payne Collection)

Bearden situated Washington within a lineage that reached back centuries, aligning his work with the makers of Gothic stained-glass windows, artists whose work depended upon light as a defining, activating force. This was not metaphor. It was method.

Washington’s process was exacting and physically demanding. He poured thin layers of plastic resin into molds, often five or six layers deep, beginning with lighter colors and building toward darker hues. Into these layers he embedded objects, African gold weights, semi-precious stones, small drawings, fragments that carried their own histories. Each layer had to cure before the next could be poured. Once complete, the surface was sanded and polished with extreme care.

Bearden noted the similarity between Washington’s approach and the glazing techniques of painters such as Titian and Tintoretto, who built luminous surfaces through repeated transparent washes. Washington’s materials were modern, even industrial, but his thinking was deeply historical.

After curing, the works were often mounted on carefully selected wood or metal, materials chosen not for convenience but for resonance. Nothing was incidental.

“Rhea”, M. Bunch Washington

Washington spoke of wanting to make rooms glow. Not simply with color contained within a frame, but with colored light spilling outward, touching floors, walls, and furniture. These works were meant to change as the day changed, to respond to sun and shadow, to time itself.

This responsiveness was not aesthetic novelty. It was philosophy.

Washington understood art as something that unfolds rather than asserts. His works resist fixed interpretation. Perspective shifts. Foreground and background dissolve. The viewer’s position matters. The light matters. Time matters.

Bearden also noted the influence of Washington’s study of Persian art and his dedication to the Bahá’í Faith, a religious tradition founded in Persia that emphasizes the unity of all religions and the responsibility to serve humanity. Importantly, Washington did not illustrate belief. He worked through it.

Symbols appear in his work, but never as declarations. The Bahá’í tradition cautions against literal representation, and Washington honored that restraint. His concepts are not imposed upon his materials. As Bearden observed, he creates with them.

That distinction matters.

Washington was an artist deeply invested in continuity, in the idea that modern methods could carry ancient values forward without dilution. His work asks for patience, not decoding. It rewards attention rather than explanation.

This approach did not make his path easier.

Like many African American artists of his generation, Washington faced institutional barriers that had nothing to do with the quality or rigor of his work. Recognition was sporadic. Representation inconsistent. Support unreliable. And yet, he persisted.

Liz de Souza (Washington), his daughter, has spoken about how her father defined success not by institutional validation but by fidelity to the work itself. The act of making, of solving artistic problems, of realizing a vision, was its own justification.

Washington worked through challenges materially and philosophically. How does resin behave? How does light move through color? How do objects retain meaning once embedded, once partially obscured? These were not obstacles to him. They were the work.

He believed that art, when made honestly, could outlast the circumstances of its creation. He often asked whether a work would remain relevant a hundred years from now. That question guided his decisions, his patience, and his refusal to compromise.

Today, Washington’s legacy is carried forward through careful stewardship. His children, Liz de Souza (Washington) and Jesse Washington, have played central roles in preserving, republishing, and contextualizing his work and writing, most notably through the republication of The Art of Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual. Their efforts ensure that Washington’s contributions are not relegated to footnotes, but remain part of an ongoing conversation.

“Pearls”, M. Bunch Washington

It is impossible to separate Washington’s artistic life from his relationship with Romare Bearden. Their friendship, mentorship, and collaboration shaped both men. Washington championed Bearden’s work when institutions would not. Bearden, in turn, recognized Washington’s seriousness, discipline, and originality.

“Yams, Please” M. Bunch Washington

Their exchange was not hierarchical. It was reciprocal.

In the next part of this series, we turn fully toward Romare Bearden himself, not as myth or monument, but as an artist whose work, like Washington’s, insists on interconnectedness, cultural memory, and the quiet authority of lived experience.

Sources and Context

Photo Credit - Melissa Hess

Primary sources

Liz de Souza (Washington), interview with Mark Rengers, 2026

Liz de Souza (Washington) and Jesse Washington, archival stewardship and republication efforts related to M. Bunch Washington via bunchwashington.com

Romare Bearden, “On the Art of M. Bunch Washington,” Off Broadway Gallery brochure, April 13, 1975

Secondary and contextual sources

M. Bunch Washington, The Art of Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual (Harry N. Abrams, 1972)

Digital Projects, Worcester Polytechnic Institute: archival materials on Washington and Bearden

Barnes Foundation archives and educational materials

Mary Schmidt Campbell, An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden

Lowery Stokes Sims, writings on institutional exclusion and African American art history

These works are not simply images. They are environments of light.” These words give great insight to his works!